During a mid-June 2013 visit to the Palais de Luxembourg, Paris, to view an exhibit of Marc Chagall (1887-1985) it became evident within minutes how much Chagall used musical icons in his works. This chance exhibit viewing has also inspired my desire to compose a suite based on these musical icons.

This aside, since returning to New York, I have researched Chagall’s life and work and learned that over a 75-year career, spanning most of the 20th century, he produced over 10,000 works of art in various media, including lithographs, canvas, water color, postcards, murals, and stained glass windows.

Writers of his art confirm that Chagall’s use of musical icons is no accident. As a youth in a Russian shtetl consisting of primarily members of religious Jews, Chagall was surrounded by musicians—mostly string players, as in the violin. In his youth, Chagall yearned to learn how to play the violin; his stronger impulse, though, was towards art.

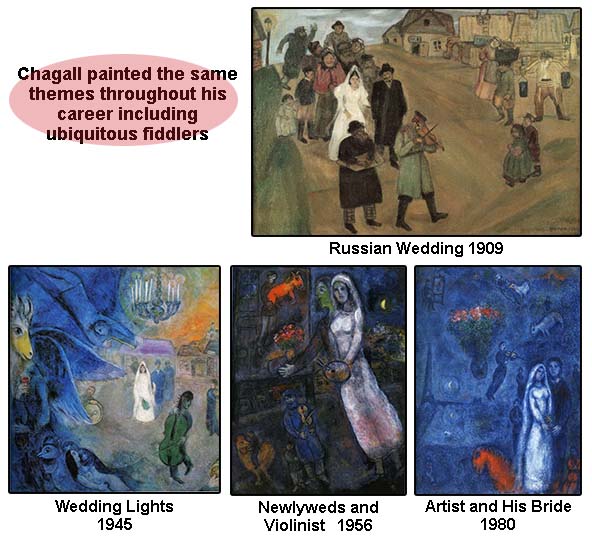

His paintings of violinists, such as “The Seated Violinist” (1908), became the basis for the iconic “Fiddler on the Roof” graphic in the poster advertising the long-running Broadway show of the same name. Mirjam Rajner, writing in the 2005 issue of Ars Judaica points out “This seemingly simple depiction of a traditional Jew playing a violin offers the basis for the complex development of a typically Chagallian theme.” Further, he writes, “As he wrote in his autobiography, in his youth Chagall himself dreamt of becoming a professional singer, violinist, or dancer—while taking singing lessons from a cantor and helping him out in the synagogue, violin lessons from a fiddler living in the same courtyard, and dancing at weddings.”

His paintings of violinists, such as “The Seated Violinist” (1908), became the basis for the iconic “Fiddler on the Roof” graphic in the poster advertising the long-running Broadway show of the same name. Mirjam Rajner, writing in the 2005 issue of Ars Judaica points out “This seemingly simple depiction of a traditional Jew playing a violin offers the basis for the complex development of a typically Chagallian theme.” Further, he writes, “As he wrote in his autobiography, in his youth Chagall himself dreamt of becoming a professional singer, violinist, or dancer—while taking singing lessons from a cantor and helping him out in the synagogue, violin lessons from a fiddler living in the same courtyard, and dancing at weddings.”

In Chagall we find the strong relationship between the musical arts, the fine arts, and deeply felt emotions. Rajner comments: “The Seated Violinist thus seems to represent the moment when a traditional, provincial Jew, after a week of labor, reconnects after the Sabbath with the spiritual world by playing a Hasidic niggun—the rabbi’s song—to express his deepest emotions.”

Michael J. Lewis, a professor at Williams College, in an article entitled “Whatever Happened to Marc Chagall?,” published by the American Jewish Committee, speculates on Chagall’s apparent fixation on musical icons, especially violinists. He writes:

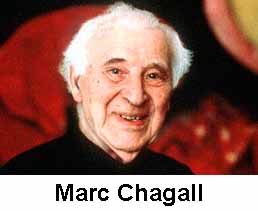

As cosmopolitan an artist as he would later become, his storehouse of visual imagery would never expand beyond the landscape of his childhood, with its snowy streets, wooden houses, and ubiquitous fiddlers. To fix the scenes of childhood so indelibly in one’s mind, and to invest them with an emotional charge so intense that it could only be discharged obliquely through an obsessive repetition of the same cryptic symbols and ideograms, would seem to require some early trauma. But nothing of the sort is related in Chagall’s copious memoirs, other than his statement that he stuttered.

Is it correct, then, that music is at the heart of all Chagall’s paintings, as playwright Rebecca Taichman−who created a musical work that drew inspiration from the “magic lyricism of Marc Chagall’s art”–has posited?

Tony Bateman, in a February 2000 article entitled “Stringing Up Paintings,” writes:

“It is an intriguing aspect of art history that a good number of the great painters were proficient string players: Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Gainsborough, Henri Matisse and the remarkable French artist Maurice Vlaminck, who could add both professional violin and double bass playing to a list of talents including novel writing and bicycle racing. . . . ‘Music is the sister of painting,’ wrote Leonardo da Vinci, and it appears that his abilities as a musician were considerable. Indeed, when Leonardo was introduced at the court of Milan in 1494, he was presented to the Duke as a performer on the lira da braccio. Leonardo’s skill as a lira player, along with his many other talents, made him the archetypal Renaissance man.”

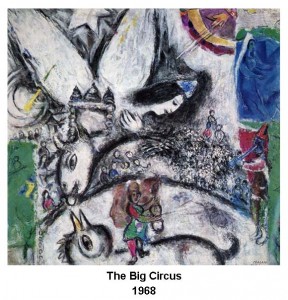

We can put Marc Chagall in this same “Renaissance man” camp. His 10,000+ artworks notwithstanding, a cursory analysis of several hundred of his artworks reveals 16 different instruments: accordion,  balalaika, cello, cymbal, flute, guitar, harp, horn, bass drum, keyboard, mandolin, saxophone, small bell, tambourine, trumpet, and violin. Further, there are several graphic references to a full circus orchestra. By far, though, the most frequently “painted” instrument is the violin, followed by the cello, and the horn.

balalaika, cello, cymbal, flute, guitar, harp, horn, bass drum, keyboard, mandolin, saxophone, small bell, tambourine, trumpet, and violin. Further, there are several graphic references to a full circus orchestra. By far, though, the most frequently “painted” instrument is the violin, followed by the cello, and the horn.

His iconic themes are also eclectic, of which there are many, including: Jewish life in the shtetl, Christian/Jewish concepts, lovers, the circus, Jewish theatre, the passage and context of time, street musicians, dancers, acrobats, et al. While many of his artworks refer to music and musicians in very subtle ways, numerous artworks have musicians as a central iconic theme, such as “The Seated Violinist,” “The Accordionist,” and “The Wandering Musicians.”

In a way, Chagall’s artworks—with their vibrant, incongruous colors and childlike fantasy images—encompass the broad range evolution of music in the 20th century. This was also the time in which jazz evolved to become a unique musical style (that the late Dr. Billy Taylor called “America’s classical music”) with a global audience. The 20th century was also a time in which classical music evolved out of the Romantic period of the 19th century into the diverse “classical” styles of the 20th century, including serial, minimalist, spectral, postmodernist, and world music, among others. It is also the century of the evolution of “popular” music: rock and roll, country and western, bebop, cool jazz, fusion, and ultimately world music.

Chagall’s art—and he is not alone in breaking with 19th century aesthetic traditions—is representative of the world turned upside down, not only in art, but in politics, business, economics, and science and technology. Chagall, who lived in two centuries, was a man and an artist representative of the rapid changes of the last 100 years.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

September 30, 2013

© Eugene Marlow 2013

Click Artsy Marc Chagall to learn more!