The Marlowsphere Blog #48

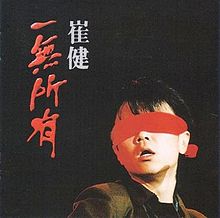

The name Cui Jian is virtually unknown in the United States, let alone in the western world. But mention his name in China and it will spur a strong response—from legions of his rock fans and from the Chinese government.

Trumpeter, lyricist, and vocalist Cui Jian (pictured left) is an icon in China’s rock world. Rock guitarist Dennis Rea, writing in his book Live at the Forbidden City (iUniverse, 2006, p. 103) describes Jian as follows:

In Post-Mao China, Cui Jian was Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and Kurt Cobain all rolled into one, a one-man rock-and-roll revolution whose moving songs of alienation spoke volumes to a generation [in China] searching for meaning in a rapidly changing and increasingly globalized China. As the reluctant spokesperson for China’s disenfranchised youth, Cui Jian will forever be linked in the public’s mind to the democracy movement that was crushed by the tanks at Tiananmen. The image of the rocker defiantly rallying hunger strikers with his stirring outsider anthems epitomized a generation’s struggles and aspirations.

Rea provides some background on this protester:

Born in 1961 to musically inclined parents of ethnic Korean descent, Cui Jian soon revealed a gift for music, and by age twenty he had landed a job playing trumpet with the prestigious Beijing Philharmonic Orchestra. . . .[However], Cui Jian had already been smitten by the rock and roll he was hearing on tapes spirited into the country by Western tourists and students. Initially inspired by the likes of Simon and Garfunkel and the rough-hewn “Northwest Wind” genre of contemporary Chinese folk music, he learned to play guitar and started singing in public, at first covering tunes by well-known singers and eventually writing his own material.

. . . .

Cui Jian released his 1986 opus “Rock and Roll in the New Long March” soon to become the defining statement of China’s new lost generation. A solid collection of original tunes, the album raised the bar for all future Chinese rock music and provided a potent and timely anthem in Cui Jian’s most enduringly beloved song, “Yi Wu Suo You”—“Nothing to My Name.” [Album cover pictured right.]

Cui Jian released his 1986 opus “Rock and Roll in the New Long March” soon to become the defining statement of China’s new lost generation. A solid collection of original tunes, the album raised the bar for all future Chinese rock music and provided a potent and timely anthem in Cui Jian’s most enduringly beloved song, “Yi Wu Suo You”—“Nothing to My Name.” [Album cover pictured right.]

Jian’s songs showed a preoccupation with such sensitive topics as individualism, sexuality, blind adherence to tradition, and, by inference, the integrity of the Chinese Communist Party. The government was not amused. He was dismissed from his Philharmonic position and at one point forbidden to perform in public for one year.

Now in this early fifties, Cui Jian is again protesting—this time not from the stage, but from the rock and roll audiences’ perspective.

According to a late November 2012 report, recounted from the China Daily, Cui has been disheartened by observing how security guards [dressed in military uniforms] tend to stop audiences from “standing up and interacting with the performers.” And so, like at many other points in time when he saw something in need of repair, he aims to step up.

“I want to have a company to train people to become real security guards,” the China Daily quotes Cui as saying. “Serving instead of controlling the audiences and guaranteeing that the audience have a good time.”

The report goes on to say

Part of that good time, of late, has involved his invitation to the more excited female fans in crowds to join him onstage as part of the finale. This, one might say, is the latest incarnation of his career-long testing of the boundaries of the live music sphere, particularly as far as security personnel have been concerned. In the past, rather than exciting fans by holding out the prospect of joining him onstage, Cui’s music, and the expression it represented, affected audiences in such deep ways that security folks were dealing with people so emotionally, and physically, affected by the music that they literally didn’t know what to do with their bodies.

This last description is remindful of film footage of “bobby-soxers” in the early Frank Sinatra era, teenagers responding to the Beatles initial visits to the United States, and Elvis Presley’s below the waist gyrations. The young women appear to be out of control.

This last description is remindful of film footage of “bobby-soxers” in the early Frank Sinatra era, teenagers responding to the Beatles initial visits to the United States, and Elvis Presley’s below the waist gyrations. The young women appear to be out of control.

“Rock music has been considered noisy and dangerous in China for the longest time. But I can tell you that rock fans are very peaceful, pure and simple, just like rock music itself,’” Cui is quoted as saying.

While a rock concert is certainly not a battleground in a military sense, it is in a cultural sense. In China adherence to a central authority is a cultural more drilled deep into the society. To be out of control is anathema to traditions that were established thousands of years ago in that part of the world.

What is amazing is that Cui Jian continues to this day to be a cultural icon whose voice of protest has not been silenced. But there are other artists who have been, but somehow have managed to get the “word” out.

This is from a very recent review of a documentary of artist Ai Weiwei:

Poor China. So isolated, so misunderstood. And why is the rest of the world always picking on it over the business of stifling personal expression and trampling human rights? Using sarcasm as a diplomatic strategy may not work very well, but in the intimately revealing documentary Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, it is doled out in equal measure with irony and outrage as a way of conveying the danger and absurdity of some of the country’s more egregiously oppressive policies. The artist and activist Ai Weiwei has been captured in unique profile by the American freelance journalist Alison Klayman, who had unfettered access to this near-heroic figure as he traveled around China and the world to promote his exhibitions and his fight for a variety of human causes, which were often one and the same. Until the government shut him up, that is, in an incident that made world headlines and that Klayman revealed as best she could after his 81 days of detention and an official gag that left his powerful voice and deliberate actions all but paralyzed.

Poor China. So isolated, so misunderstood. And why is the rest of the world always picking on it over the business of stifling personal expression and trampling human rights? Using sarcasm as a diplomatic strategy may not work very well, but in the intimately revealing documentary Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, it is doled out in equal measure with irony and outrage as a way of conveying the danger and absurdity of some of the country’s more egregiously oppressive policies. The artist and activist Ai Weiwei has been captured in unique profile by the American freelance journalist Alison Klayman, who had unfettered access to this near-heroic figure as he traveled around China and the world to promote his exhibitions and his fight for a variety of human causes, which were often one and the same. Until the government shut him up, that is, in an incident that made world headlines and that Klayman revealed as best she could after his 81 days of detention and an official gag that left his powerful voice and deliberate actions all but paralyzed.

The issues of China’s oppression of Tibet notwithstanding, even more recently (as in the last few days), it has been revealed that Chinese operatives have hacked into the electronic files of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

According to Tom Gara’s review of The New Digital Age, (Random House) which debuts in April, authors Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt together with Jared Cohen, a 31-year old former State Department big shot who now runs Google Ideas, the search giant’s think tank, China. . .“is the world’s most active and enthusiastic filterer of information” as well as “the most sophisticated and prolific” hacker of foreign companies. In a world that is becoming increasingly digital, the willingness of China’s government and state companies to use cyber-crime gives the country an economic and political edge, they say.

According to Tom Gara’s review of The New Digital Age, (Random House) which debuts in April, authors Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt together with Jared Cohen, a 31-year old former State Department big shot who now runs Google Ideas, the search giant’s think tank, China. . .“is the world’s most active and enthusiastic filterer of information” as well as “the most sophisticated and prolific” hacker of foreign companies. In a world that is becoming increasingly digital, the willingness of China’s government and state companies to use cyber-crime gives the country an economic and political edge, they say.

Gara further writes,

But for all the advantages China gains from its approach to the Internet, Schmidt and Cohen still seem to think its hollow political center is unsustainable. “This mix of active citizens armed with technological devices and tight government control is exceptionally volatile,” they write, warning this could lead to “widespread instability.”

In the longer run, China will see “some kind of revolution in the coming decades,” they write.

Perhaps Schmidt, Cohen, and Gara have not heard of Cui Jian. He has been protesting for more than a generation—and inside China yet! Jian’s protest is a protest against the outcomes of the Mao-ist revolution, and of the post-Mao government still clinging to out-moded traditions. Ironically, even with the opening up of China economically following Mao’s passing in 1976, the Chinese Communist Party won’t or can’t let go of the central authority concept.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

February 4, 2013

© Eugene Marlow 2013