The following blog is excerpted from my forthcoming book on jazz in China, Jazz in the Land of the Dragon. Much of what follows is excerpted from Willie Ruff’s memoir A Call to Assembly: The Autobiography of a Musical Storyteller (Viking Penguin, 1991).

*************************************************************

“The story of jazz in China first seduced me in the 1950s, when I learned that trumpeter Buck Clayton and trombonist Dickie Wells had played in a Shanghai British men’s club in 1937,” said Willie Ruff–not only the first African-American jazz musician to travel to Shanghai to perform following Mao’s death, but also reportedly the first jazz musician from anywhere on the planet to step onto China’s shores.

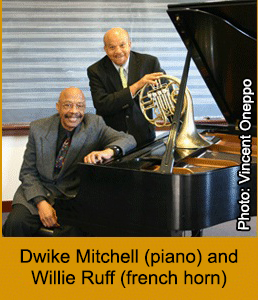

A long-time professor and founder of the Duke Ellington Fellowship program at Yale School of Music, Ruff is one half of the Mitchell-Ruff Duo with pianist and friend Dwike Mitchell. In 1959, the pair “introduced jazz to the Soviet Union, playing and teaching in Russian conservatories, and in 1981 they did the same in China.”

In his 1991 memoir, A Call to Assembly— it received the ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for excellence in a book on music–Ruff revealed his connection with Shanghai and how his interest began: “When Beijing and Shanghai natives began arriving in my classroom believing that the Stephen Foster they’d heard back home was jazz, I knew it was time to knock on the door of Yale’s Chinese Department.”

The bass and French horn player immediately began studying Mandarin and soon Ruff was known as the “strange black music man in New Haven” who “wouldn’t shut up in Chinese.” At the same time, Chinese interest in American music was flourishing. One day, Ruff received a call from Professor Tan Shu-chen, deputy director of the Shanghai Conservatory, wishing to see Yale and needing a host. Ruff accepted.

Professor Tan Shu-chen was born in Shanghai in 1907, learned European languages and music, and by 1930, was teaching in six Shanghai colleges. But from 1966 to 1976, Western music of all kinds had been silenced in China and the Professor Shu-chen, like all teachers in the People’s Republic of China, was publicly humiliated and accused of being a “tool of decadent cultural influences from the West.”

Professor Tan Shu-chen was 73 years old when he visited Yale. Ruff compared his face to “a composite of all the good teachers” he’d ever known. He invited Professor Tan Shu-chen to attend a performance of the Mitchell-Ruff duo for undergraduate Yale students. Afterwards, Ruff detected Professor Tan Shu-chen’s fascination with improvisation. When he left Yale, he insisted that Ruff and Mitchell visit his conservatory if they ever made it to Shanghai.

Ruff soon took Professor Tan Shu-chen up on his offer. He applied for a travel grant from Coca-Cola, received a check and, with Mitchell, travelled to Shanghai in 1981. Upon arriving, Professor Tan Shu-chen asked the duo to play a concert the next day. They happily agreed.

“There were about three hundred students and their teachers sitting in the informal concert space the next day,” Ruff recalled of their performance on June 2, 1981. Professor Tan Shu-chen introduced the duo and announced that Ruff would be addressing them in Chinese. “My first words were an apology and a plea for their patience with the poor Chinese of a foreigner who wanted passionately for them to know his people’s music. Their friendly applause relaxed me, and I went to work.” Ruff explained the music created by black people in America and the importance of the drum in West African music, comparing the drum in West African society to the book in literate society. He told the story of when the Africans were brought to America as slaves and their drums were taken from them, because their slave owners feared its power. “While no instrument can replace the drum, we developed musical devices that can be thought of as drum substitutes,” Ruff elucidated.

“There were about three hundred students and their teachers sitting in the informal concert space the next day,” Ruff recalled of their performance on June 2, 1981. Professor Tan Shu-chen introduced the duo and announced that Ruff would be addressing them in Chinese. “My first words were an apology and a plea for their patience with the poor Chinese of a foreigner who wanted passionately for them to know his people’s music. Their friendly applause relaxed me, and I went to work.” Ruff explained the music created by black people in America and the importance of the drum in West African music, comparing the drum in West African society to the book in literate society. He told the story of when the Africans were brought to America as slaves and their drums were taken from them, because their slave owners feared its power. “While no instrument can replace the drum, we developed musical devices that can be thought of as drum substitutes,” Ruff elucidated.

Professor Tan Shu-chen had asked Ruff and Mitchell to explore improvisation for the students, and with no exact Chinese translation to define the word—there is no word for improvisation in Chinese–Ruff settled for, “something created during the process of performance,” and the rest was as follows.

Mitchell whispered, “Let’s make up one. You start on the horn.” Ruff continued, “I didn’t even tell the audience what was coming. I just played the first theme that popped into my head: nothing grand, no virtuoso flash or dazzle. Any student there could have thought up its simple four- or five-note design and played it on its own instrument. As I blew on, Mitchell played a countermelody to match the horn’s. I caught it and turned it around, and we exchanged parts, supported one another and entered into the nip and tuck, the call and response, the pauses and the breaks, of the improviser’s game.

Ruff adds: “Improvising is interesting and exhilarating. It is art so thoroughly complex and difficult that it engages all your instincts and intelligence. Doing it before an audience always heightens the stakes; if you play to teach, the stakes automatically double. Putting forth a new musical thought means putting something personal on the line. It is the ultimate gamble; you stick your neck out, push the limits, pace yourself, and learn what to leave out. The overworked myth that improvising jazz means ‘going wild’ and ‘letting it all hang out’ is just that, myth. It’s no cinch to make musical sense spontaneously. There is discipline, and there are rules.

“When the number ended, I told the audience, ‘This is the newest music you have ever heard. I can be sure of that, because we just made it up right here, right now. We call it ‘Shanghai Blues.’

Bedlam. Roaring applause, cheers, and approval.”

Professor Tan Shu-chen started taking questions at once: “When you created ‘Shanghai Blues’ just now, did you have a form for it, or logical place? Could two total strangers improvise together? Could a Chinese person improvise?”

Ruff invited students to play pieces of their own and he and Mitchell would try to make jazz out of it. A young man was called to the stage and, after some coaxing, went to the piano. As he played, Ruff observed the scene:

“I sensed Mitchell fastening his concentration on that flavor, his emotional radar homing in on the music’s essence and telling him the secrets of its ‘Chineseness’ and its spirit. And then, after about a dozen bars, the perfectly constructed little piece came to its pleasant and unexpected conclusion.

“The audience went berserk.

“It was the moment I’d waited years for. If the game were golf, smart money would be on the kid from Dunedin, Florida. Mine was on a hole in one. I just stood there holding the bass, waiting. I saw Mitchell’s eyes surveying the keyboard as he sat down. He took a moment to map his course. Nothing stirred on the stage, or anywhere in the hall.

“Suddenly the Steinway rang out with the exact notes the students had played. No one-finger pick-out-the-tune. There, in full cry, were the composer’s big two-fisted chords, complete with his melody and, more important, with all his original expression.

“A youthful Chinese voice in the audience cried out, “That American is a human tape recorder!”

Professor Ruff is still teaching at Yale to this very day.

A video of that historic performance can be found at http://www.willieruff.com/.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

December 17, 2012

© Eugene Marlow 2012