- A journalist is killed in the line of duty somewhere around the world once every eight days.

- Nearly three out of four are targeted for murder. The rest are killed in the crossfire of combat, or on dangerous assignments such as street protests.

- Local journalists constitute the large majority of victims in all groups.

- The murderers go unpunished in about nine out of 10 cases.

- The overall number of journalists killed, and the number of journalists murdered, have each climbed since the 1990s.

(Source: Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) Blog November 13, 2012 entry http://cpj.org/security/2012/11/will-un-plan-address-impunity-security-for-journal.php#more)

At the Newseum in Washington, D.C., there is a permanent Freedom Forum Journalists Memorial dedicated to the 2,156 journalists who have died in the pursuit of their chosen profession. This floor-to-ceiling exhibit is re-dedicated every year.

In 2012, 51 journalists–reporters, photographers, broadcasters–in 16 countries have lost their lives (so far) practicing their profession. The two leading countries in terms of number of journalistic casualties are Somalia (10) and Syria (21).

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), 950 journalists have been killed in the line of duty since 1992. The beats these journalists covered included business, corruption, crime, culture, human rights, politics, sports, and war.

The 20 deadliest countries (in descending order) are Iraq, Philippines, Algeria, Russia, Somalia, Pakistan, Columbia, India, Mexico, Afghanistan, Syria, Brazil, Turkey, Sri Lanka, Bosnia, Tajikstan, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Bangladesh, and Thailand.

One glance at the press freedom map maintained on the Newseum’s web site makes vivid that much of the world’s population does not enjoy freedom of the press as guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The map also coincides to a very large degree with the places where journalists have lost their lives.

One glance at the press freedom map maintained on the Newseum’s web site makes vivid that much of the world’s population does not enjoy freedom of the press as guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The map also coincides to a very large degree with the places where journalists have lost their lives.

On November 20, the Committee to Protect Journalists hosted a gala (its 22nd) at New York City’s Waldorf Astoria to honor several journalists and to raise funds for its various activities. I was privileged to attend the event as a member of the press.

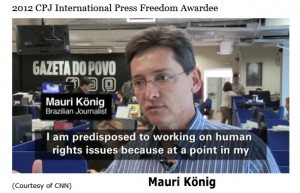

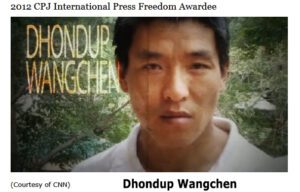

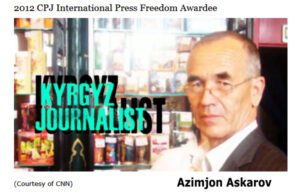

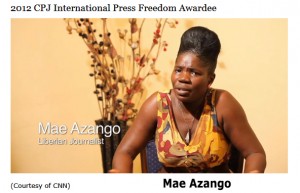

Four journalists who risked their lives and liberty to reveal abuses of power and human rights violations in Brazil, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Liberia were honored with the Committee to Protect Journalists’ 2012 International Press Freedom Awards, an annual recognition of courageous reporting.

The awardees—Mauri König (Gazeta do Povo, Brazil), Mae Azango (FrontPage Africa and New Narratives, Liberia), and jailed journalists Dhondup Wangchen (Filming for Tibet, China) and Azimjon Askarov (Ferghana News and Golos Svobody, Kyrgyzstan)—have faced severe reprisals for their work, including assault, threats, and torture. Askarov is serving a life sentence in connection with his coverage of official corruption, and Wangchen is serving a six-year prison term following his documentation of Tibetan life under Chinese rule.

CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon, pointed out from the podium that “Two [journalists]—Azimjon Askarov and Dhondup Wangchen—have actually been arrested and jailed for their critical reporting. We will not rest until they are free.” Simon also pointed out that the country with the largest number of jailed journalists is Turkey, a country geographically linking Europe with Middle East that has a democratically elected government. Its practices with respect to freedom of the press is, however, less than democratic.

PBS senior correspondent and CPJ board member Gwen Ifill hosted the event. The dinner chairman was David Boies, chairman of the law firm Boies, Schiller & Flexner LLP.

With respect to the awardees,

Mauri König, one of Brazil’s premier investigative journalists, has spent 22 years reporting on human rights abuses and corruption. König’s work includes a series of articles in late 2000 and 2001 that documented the recruitment and kidnapping of Brazilian children for military service in Paraguay. While researching the story in Paraguay, König was brutally beaten with chains, strangled, and left for dead. In 2003, he faced a wave of threats from police as he reported along the Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina border area. Neither case was ever resolved.

Mauri König, one of Brazil’s premier investigative journalists, has spent 22 years reporting on human rights abuses and corruption. König’s work includes a series of articles in late 2000 and 2001 that documented the recruitment and kidnapping of Brazilian children for military service in Paraguay. While researching the story in Paraguay, König was brutally beaten with chains, strangled, and left for dead. In 2003, he faced a wave of threats from police as he reported along the Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina border area. Neither case was ever resolved.

Dhondup Wangchen is a self-taught Tibetan documentary filmmaker who conceived and shot the film “Leaving Fear Behind” to portray life in Tibet in advance of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Shortly after his footage was smuggled overseas, Wangchen disappeared into Chinese detention. Knowledge of his whereabouts came only after Jigme Gyatso, a monk who had helped shoot the film, was released from jail. Wangchen was sentenced to six years in prison, and in January 2010, he was denied appeal.

Dhondup Wangchen is a self-taught Tibetan documentary filmmaker who conceived and shot the film “Leaving Fear Behind” to portray life in Tibet in advance of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Shortly after his footage was smuggled overseas, Wangchen disappeared into Chinese detention. Knowledge of his whereabouts came only after Jigme Gyatso, a monk who had helped shoot the film, was released from jail. Wangchen was sentenced to six years in prison, and in January 2010, he was denied appeal.

Azimjon Askarov, a Kyrgyz journalist and human rights defender, is serving a life term in prison in connection with his coverage of official wrongdoing and abuse. His conviction—following a judicial process marred by torture, lack of evidence, and fabricated charges—has been challenged by human rights organizations and the Kyrgyz government’s own ombudsman’s office. Askarov was charged with complicity in an officer’s murder and a series of anti-state crimes, but a CPJ special report, based on interviews with the journalist, his lawyers, and witnesses, has shown that no material evidence or independent witnesses were presented in court to support any of the charges.

Azimjon Askarov, a Kyrgyz journalist and human rights defender, is serving a life term in prison in connection with his coverage of official wrongdoing and abuse. His conviction—following a judicial process marred by torture, lack of evidence, and fabricated charges—has been challenged by human rights organizations and the Kyrgyz government’s own ombudsman’s office. Askarov was charged with complicity in an officer’s murder and a series of anti-state crimes, but a CPJ special report, based on interviews with the journalist, his lawyers, and witnesses, has shown that no material evidence or independent witnesses were presented in court to support any of the charges.

Mae Azango is one of a small number of female reporters working in Liberia. For the past 10 years, she has worked to expose the plight of ordinary people, particularly women and girls, who have been victimized by issues long hushed in her society. In 2012, Azango took on the politically sensitive subject of female genital mutilation, drawing threats that forced her and her daughter into hiding for weeks. Throughout, she continued to report on the practice, ultimately forcing the government to declare they would work to stop the dangerous practice.

Mae Azango is one of a small number of female reporters working in Liberia. For the past 10 years, she has worked to expose the plight of ordinary people, particularly women and girls, who have been victimized by issues long hushed in her society. In 2012, Azango took on the politically sensitive subject of female genital mutilation, drawing threats that forced her and her daughter into hiding for weeks. Throughout, she continued to report on the practice, ultimately forcing the government to declare they would work to stop the dangerous practice.

The Burton Benjamin Memorial Award was presented to Alan Rusbridger who has been the editor of the Guardian since 1995, making the U.K. newspaper a leader in international reporting and a champion of press freedom. Whether in courtrooms or online, Rusbridger has defended the right to investigate and publish stories in the public interest. Guardian.co.uk is consistently ranked among the top news websites in the world. The award is named in honor of Burton Benjamin, the CBS News senior producer and former CPJ chairman who died in 1988.

All in all, the awards ceremony at the Waldorf-Astoria was a star-studded, black-tie event with major corporations—Sony Corporation of America, Goldman Sachs, et al—buying tables. Many well-known print and electronic journalists and media executives were in attendance. It was certainly a glitterati occasion.

In addition to the awards, $1.6 million was raised from the diner tickets and the fund-raising that took place immediately after the awards were presented. The starting request was for anyone who wished to write a check for $5,000 on the spot!

The high tone, journalistic celebrity factors aside, the event underscored the impact of media on society. The expression that the pen is mightier than the sword was never made clearer than the work of the four journalists honored at the November 20th event. When journalists have access to the truth, or more importantly, when they relentlessly find ways to get to the truth, and are able to distribute this truth, either in print or electronically, then certainly these words—whether read, heard, or seen—can have the power to make change.

At the same time, though, this journalistic pursuit has a price. Sometimes the price is harassment, sometimes imprisonment, sometimes murder.

The more people have access to print and electronic media, the more social and political change is possible. But there are forces working against social and political change. These forces include highly entrenched social patterns and governments unwilling to give up their elite power positions. It is human nature not to make change. Resistance to change is formidable. Nonetheless, when journalists can tell the truth often enough, then there is a potential for change in the interest of the many.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

November 26, 2012

© Eugene Marlow 2012